Do you live in an apartment building in a busy coastal area? Marine radars increase the likelihood of Wi-Fi congestion for nearby networks.

In short

Apartment buildings along the coast in areas where there is a lot of ship traffic often struggle with a complex mix of Wi-Fi problems.

- Maritime radar blocks parts of the 5 GHz frequenxy band and increases the likelihood of congestion / overload

- High numbers of connected clients (mobile phones, computers and other devices) on the same Wi-Fi channels lead to congestion.

- A high density of “competing” networks creates interference.

About channels and frequencies

Wireless internet (Wi-Fi) uses two frequency bands:

- 2.4 GHz

- 5 GHz

Each frequency band is divided into smaller areas called channels. When there are multiple Wi-Fi networks in close proximity to each other, the ideal is for these networks to make use of wireless channels that do not overlap. When (too) many clients are connected on the same channel, this can create Wi-Fi congestion – overload – and very poor performance on the networks.

You can set up which channel a wireless network should use, but in most cases it is better to leave this decision to the Wi-Fi equipment itself. In some cases it is even legally required for them to change channels.

Radar and Dynamic Frequency Selection (DFS)

Radar technology is used, among other things, in marine navigation to detect obstacles, avoid collisions, and so on. This technology uses some of the same frequencies as wireless internet.

This means that wireless networks can create interference for the radar, which is why anyone who produces Wi-Fi equipment is required by law to make sure their equipment does not get in the way of radars.

Simply put: The channels used for radar can also be used by Wi-Fi, as long as Wi-Fi moves as soon as a radar is nearby.

This is solved in most routers and other wireless access points by a functionality called DFS – dynamic frequency selection. When the device detects a radar, other connections are automatically moved onto different channels on the 5 GHz frequency band so as not to interfere with the radar.

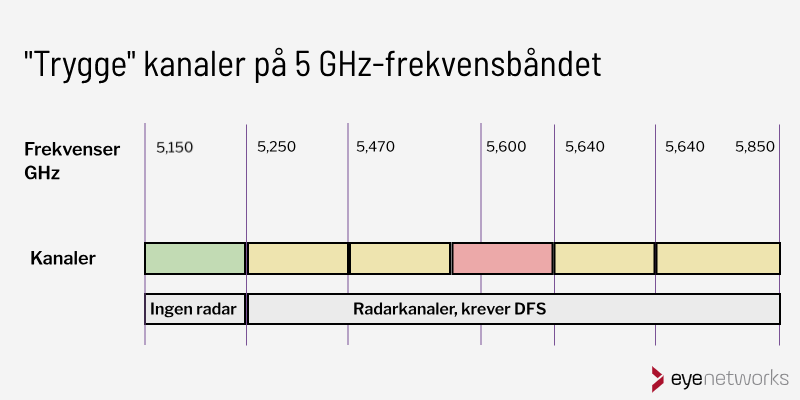

Five (non-overlapping) channels on the frequency band illustrated above are reserved for radars. The illustration shows 80 MHz channels, which is what mesh Wi-Fi uses.

Two of them – those marked in red on the illustration – require a radar scan for 10 minutes before you are allowed to connect to them. This is so impractical that many Wi-Fi manufacturers choose not to to use these channels at all, because the network would otherwise be unavailable for 10 minutes at a time.

The channels marked in yellow on the illustration require radar scanning for 1 minute, and these are the channels we refer to when we are talking about dynamic frequency selection.

The channel area marked in green is never used by radar, and that’s where all connected clients are moved when a radar is detected.

However, when many people are moved to the same channel at the same time, there is a high risk of congestion.

High Network Density Creates Interference

Any wireless network nearby can cause noise or interference to a Wi-Fi network. This applies to the neighbor’s Wi-Fi, which of course has the most impact when there are many smaller residences grouped closely together.

But additional Wi-Fi networks within the same household can also be a source of noise – for example if you have Wi-Fi running on a multi-function gateway in addition to a Wi-Fi mesh network.

Article by Geir Arne Rimala and Jorunn Danielsen