Wifi went from unknown to indispensable in 20 years. Where did wifi come from? Who should we be thanking?

The first communication networks were both wireless and pre-industrial: smoke signals, light and flame signals, mirrors, signal shots, and flags are all examples of technologies that have been used for the wireless transfer of information, starting long before the telegraph and the telephone brought wires into long-distance communication.

Hertz, Bose, and the Invisible Light

The radio became the first wireless technology of the industrial age. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz made the first properly documented transmissions of electromagnetic waves in the 1880s. Later, of course, Hertz became the very name of the unit for measuring frequencies.

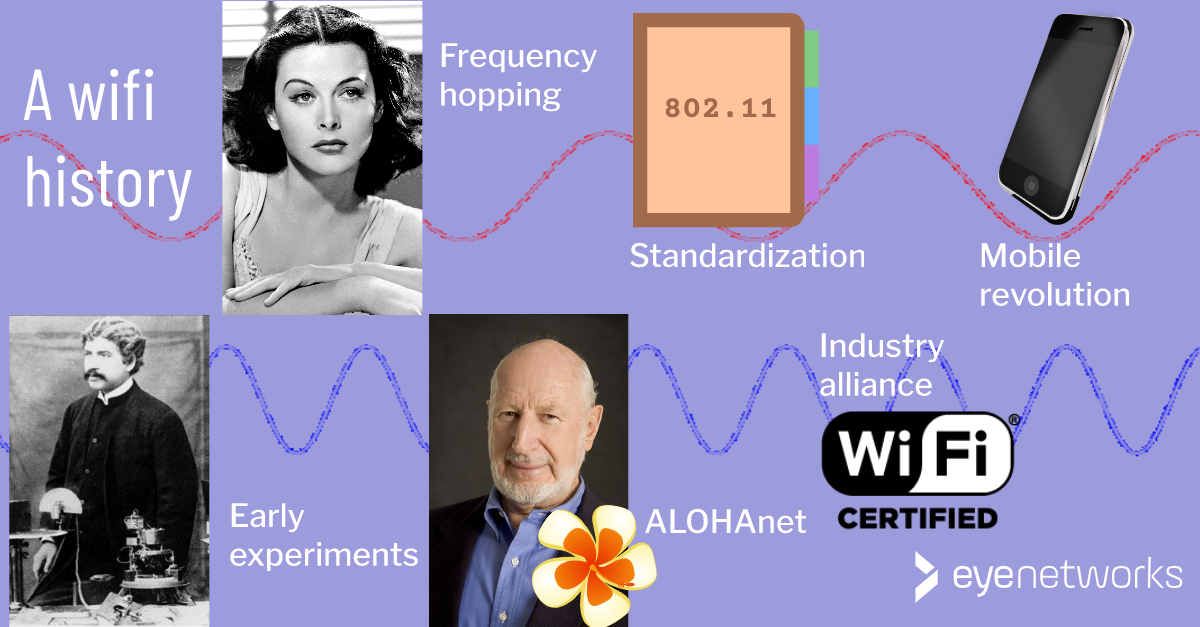

Serbian-American Nikola Tesla and Bengali Jagadish Chandra Bose were two of many scientists that continued the work Hertz had done with radio waves.

In the 1890s, Bose famously demonstrated microwaves by using them to ignite gunpowder and ring a bell at a distance, in front of an audience in the town hall of Kolkata.

In his essay “Invisible Light”, Bose wrote:

The invisible light can easily pass through brick walls, buildings etc. Therefore, messages can be transmitted by means of it without the mediation of wires.

Towards the turn of the century, Guglielmo Marconi introduced the first commercially usable apparatus for wireless long-distance telegraphy–building on the work of, among others, Hertz, Tesla, and Bose.

Tesla’s Method

Nikola Tesla was also behind the first known method for changing frequencies to avoid interference. In 1903 he patented a system where the transmitter and the receiver switch synchronously between two channels.

Like any groundbreaking communication technology this, too, soon found a military use. From 1915, the German military started using radios with changing frequencies to prevent the British from eavesdropping.

Hedy, Bad Boy George, and the Torpedoes

Hollywood star Hedy Lamarr was sharp, inventive, and had a decidedly wide range of interests. She was the one who would come to take this technology further.

She developed her contribution to wifi history together with avant garde composer George Antheil, who had referred to himself as “the bad boy of music”.

Lamarr was familiar with both radio technology and the weapons industry. She knew that torpedoes were effective weapons, but highly vulnerable to the detection and sabotage of the radio signals used to control them. She had the idea of using multiple, changing frequencies to make signal sabotage harder, and referred to it as frequency hopping. This is an early example of what is now known as spread spectrum technology.

From musical projects, composer Antheil had extensive experience with the synchronization of player pianos, or pianolas. The two took inspiration from this to develop a secret communication system for the remote control of torpedoes, based on a frequency hopping mechanism that switched between 88 different frequencies. In 1942, they received a patent for this system.

However, the American navy proved unenthusiastic about the proposed apparatus for making use of this system, and so did not adopt it at the time. Only much later, after the original patent had expired, someone finally put their invention to use for military purposes.

In 1997, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) awarded Lamarr and Antheil (posthumously) their Pioneer Award for the inventors’ “trail-blazing development of a technology that has become a key component of wireless data systems”.

Lamarr passed away in 2000. The animation below was made by Google for her 101st birthday in 2015:

ALOHAnet

Packet radio is a radio communication technology that sends data as packets. The first packet radio network was developed at the University of Hawaii in 1971. ALOHAnet connected seven campuses on four different islands, ensuring that they could all communicate with each other through a central computer located on the island of Oahu. The group that developed the network was headed by Professor Norman Abramson.

ALOHAnet also gained interest with the US military and DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), who came to develop multiple networks based on packet radio, for tactical field communication usage, among others. This was during the same time that DARPA was developing ARPANET, now known as the predecessor of the internet.

Packet radio networks gained some traction in the private market as well, but was never a commercial success–transmission speeds were too low, costs were too high, and the selection too small. Today, amateur/HAM radios are the most common use for packet radio.

Many manufacturers opted for the cabled Ethernet technology, that was available from the early 80s, rather than the slow and expensive packet radio. Soon, brand new wireless possibilities were to open up.

Opening Up the Garbage Bands

In 1985, FCC, the US telecommunication authorities, chose to open up three frequency bands on the wireless spectrum for unlicensed use.

Those bands, also known as “the garbage bands”, were 900MHz, 2.4 GHz, and 5.8 GHz.

These bands were already in use for, among other purposes, microwave ovens, that cook food using radio waves. The condition for using these bands for communication purposes, was therefore being able to work around interference from other equipment using spread spectrum technology – such as frequency hopping.

Vendors quickly started developing their own, proprietary solutions that communicated using these frequencies. While some of them worked just fine on their own, the obvious weakness was the lack of communication across solutions.

Enter Standardization

Vendors therefore slowly came to see the need for a shared wireless standard, much like Ethernet had become a successful industry standard for wired network communication.

A committee of the organization Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) develops the Ethernet standard, and so the vendors contacted IEEE to discuss the possibility of forming a brand new standards committee for wireless communications.

The new committee started work in 1990 under the catchy name “802.11”. This number remains a part of the name of every standard the committee releases.

The committee finally agreed on and released the first of those standards in 1997. The first 802.11 standard used frequency hopping and provided a data transfer capacity of 2 megabit per second.

New and improved versions of the standard came out fairly frequently in the years that followed. In newer standards, direct sequence—a different spread spectrum technology—also replaced frequency hopping.

The Origin of “Wi-Fi”

Technical standards are voluminous documents. Once people start implementing these standards, they often interpret them differently, and this happened with the 802.11 standard, too.

In 1999, six major vendors therefore founded a new industry alliance to improve cross compatibility.

The new alliance had a great cause, but they were in need of a good name, both for themselves and for the standards they were going to promote. They hired branding consultants to find a name that was “a little more catchy than ‘IEEE 802.11b Direct Sequence’”.

The consultants proposed “Wi-Fi” as a riff on “hi-fi”, borrowed from the world of music. No, it was never meant to be an acronym or abbreviation. Wifi is in fact not short for anything at all, despite the occasional unsuccessful attempt to introduce such terms as “wireless fidelity”.

The term “Wi-Fi” itself, however, caught on quickly, and it stuck.

The new industry association became the Wi-Fi Alliance, and today hundreds of technology vendors are part of this alliance. The alliance promotes wireless technology, protects “Wi-Fi” as a brand and seal of approval, and certifies wireless products.

When it comes to developing the standards, however, IEEE committee 802.11 is still in charge.

Portable Goes Wireless, and Wireless Takes Off

In 1999, Apple introduced the iBook G3, which became the first laptop with integrated Wi-Fi made for consumers. The iconic laptop had a characteristic shape and colors that prompted people to compare it to both Barbie accessories and toilet seats.

Laptop PCs with wifi soon followed, and the first mobile phones certified by the Wi-Fi Alliance were introduced in 2004. One of the earliest models was the Nokia 9500 Communicator. One of the earliest was Nokia’s 9500 Communicator.

Since the iBook, the number of connected gadgets has snowballed, and Wi-Fi has become the most common way of connecting.

In 2015, the 802.11 committee created a series of short YouTube videos to mark their 25th anniversary. In the video below, committee member Dave Bagby explains how low the interest in wireless was when they first started working on the standard. He also reveals what he think has been its most critical success factor.

We designed it for mobility.

Dave Bagby

What next?

Today, almost everyone has at least one device that can send and receive data wirelessly–in fact, most of us have several.

In a Norwegian survey from 2016, 25% reported using five or more devices connected to the internet on a daily basis. 46% used three or four connected devices. Only 3% reported not to have any connected devices at all.

The advent of smart home technology and the Internet of Things even has our homes and interiors using wifi on their own.

When a lot of devices are fighting for wireless capacity, wifi can quickly become a bottleneck.

Is this happening to you?

We recommend having a look at the tips and tools we have gathered here at Wifi Central.

More Sources / References

Most sources are linked directly in the article above, but information is also taken from:

June 1941: Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil submit patent for radio frequency hopping (American Physical Society News)

A Brief History of Wi-Fi (The Economist)

History of Wireless Communication (Seymour and Shaheen, Review of Business Information Systems)

Article by Jorunn Danielsen